The discourse on gender discrimination in Pakistan often struggles to achieve meaningful outcomes due to deeply entrenched patriarchal norms that prioritize male authority and control.

These societal norms influence attitudes and behaviours, leading men to resist acknowledging and tackling issues concerning women's rights and preventing women from advocating for their own rights on equal platforms.

Additionally, fear of change among those benefiting from current power dynamics and a lack of education about gender issues contribute to misunderstandings and biases.

The Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (2010) claims that while women are granted certain legal rights according to the Constitution, such as property rights, freedom of movement, access to education, and the right to marry with consent without gender discrimination, societal pressures and traditional customs typically prevent them from exercising these rights in practice.

Moreover, in discussions, the majority of men manipulate language to undermine feminist arguments, using derogatory terms or framing issues as less significant. Social stigma and backlash against advocates for gender equality also create hostile environments for open dialogue.

Cultural and religious influences further complicate the dialogue, with interpretations that sometimes reinforce gender inequality and resistance to feminist perspectives.

In Pakistan, men use the intersection of manipulative interpretation of religion and prevalent patriarchal traditions to deprive women of their educational, legal, and economic rights.

Islamic teachings emphasize the importance of education for both men and women. However, men often misinterpret or selectively highlight certain aspects to discourage women's education.

Men argue that women's primary role is within the home, citing religious teachings that emphasize modesty and traditional gender roles. They argue that educating women might expose them to non-Islamic values or environments that could undermine their modesty and morality, values that they ironically disregard when convenient.

These beliefs when perpetuated in a community lead to early marriages, where girls are pulled out of school to become homemakers, further curtailing their educational prospects. Additionally, there is often a lack of investment in female education infrastructure, particularly in rural areas where poverty rates are high and literacy rate of women low, justified by the notion that educating girls is less important than educating boys.

Literacy rates of Pakistan, according to a survey of 2019, demonstrate a substantial gender gap, with men at 69.29% and women at 46.49%. Approximately 12 million girls are out of school, reflecting societal priorities and constraints on female education.

Educational curricula also often reflect gender biases, with textbooks portraying women in traditional roles and men in positions of authority. A study, Exploring the Representation of Gender and Identity, based on textbooks of Sindh by Agha, Syed, & Mirani (2018) elucidates that stereotypical gender roles are quite evident in the pictorial form of textbooks assigned to primary schools in Pakistan. In these pictures, women are presented as secondary and dependent characters.

Consequently women are deprived of employment opportunities that men find much easier to obtain. Employment issues for women in Pakistan are deeply intertwined with cultural and traditional beliefs that prioritize men's roles in the workforce while confining women to domestic spheres. This perspective discourages women from seeking employment. Even when women do enter the workforce, they face significant challenges, including pay gaps, harassment, limited career advancement opportunities, and discrimination.

In many workplaces in Pakistan, cultural norms and religious beliefs influence policies that disadvantage women. For example, lack of maternity leave, child care, and flexible working hours are crucial for women balancing work and family responsibilities.

While men fail to acknowledge their leverage in every aspect of life in Pakistan, women suffer everywhere. More often than not, women are objectified and subjected to male gaze. They are appreciated for their beauty, but never for their competency and fortitude. They are also underrepresented in leadership positions, with societal expectations and biases hindering their professional growth.

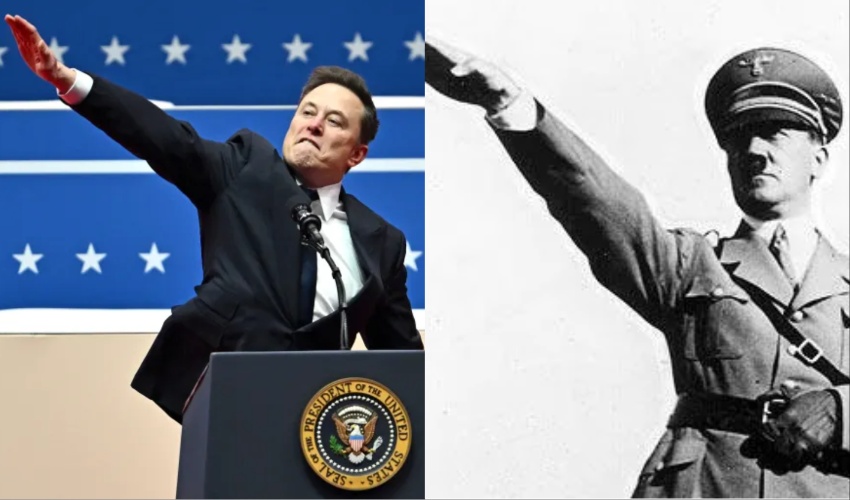

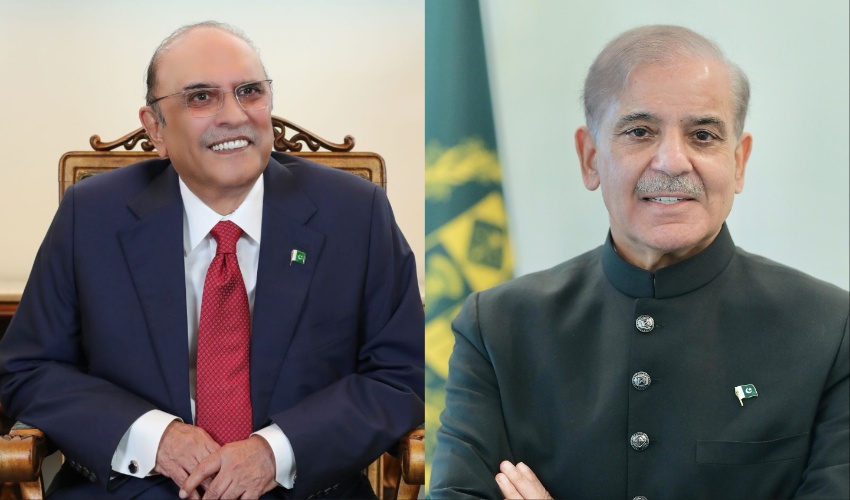

This under-representation is evident in politics also, as Pakistan has had 23 prime ministers since Independence, but only one of them has been a woman, Benazir Bhutto. There have also been 31 chief ministers, with Maryam Nawaz being the only woman to hold the position.

The percentage of female employees varies significantly across provinces. In Punjab, women constitute 57% of the workforce, while in Sindh, they make up 22%, in KP 8.92%, and in Balochistan only 3.19%. These figures suggest that cultural and ethnic norms within provinces significantly impact women's participation in the workforce.

Moreover, women's economic participation is further restricted by legal and structural barriers designed by men. Inheritance laws, when interpreted through a patriarchal lens, ensure that economic power remains concentrated in the hands of men. Women also face difficulties in accessing credit and financial services, limiting their ability to start or expand businesses. The informal sector, where many women work, is characterized by low wages, poor working conditions, and a lack of job security.

In Pakistan, men employ conservative interpretations of Islam to emphasize a woman's role as a mother and home-maker, often at the expense of her individual health needs. This perspective leads to inadequate prenatal and postnatal care, high maternal morbidity and mortality rates, and a general neglect of women's health issues. Women frequently require permission from male family members to seek medical care, which can delay treatment and exacerbate health problems.

Additionally, there is a lack of female healthcare providers, especially in rural areas, due to cultural norms that discourage women from pursuing careers in medicine. This shortage makes it difficult for women to access gender-sensitive care, further compromising their health.

Moreover, harmful practices such as karo kari (so-called honour killing), vani (marriages to settle disputes), and marriage to the holy Quran (a custom in some areas to avoid property division) perpetuate gender discrimination. The lack of legal action against rape and other forms of gender-based violence underscores the systemic neglect of women's rights.

In legal disputes, women face significant obstacles due to biased interpretations of Shariah law practised by men, where their testimonies are often considered less credible than those of men. This disparity is exacerbated by the under-representation of women in the judiciary, further skewing legal interpretations and decisions against women's interests.

According to the Law and Justice Commission of Pakistan, out of the 126 judges in the superior judiciary, only seven are women, and in the Supreme Court, there are just two women judges. This stark under-representation reflects deep-rooted gender biases within the legal system.

It is to be noted that true Islamic teachings, cultural evolutions and discourses built by feminist activists in Pakistan support gender equality. These reformers highlight the rights granted to women in the Islam, challenging patriarchal interpretations and advocating for women's education, legal equity, and economic empowerment.

Despite all the continuous effort, there is a severe lack of gender sensitization and awareness regarding gender discrimination, further solidifying these biases. Interpretations of Islamic principles often emphasize traditional gender roles, influencing societal expectations and legal practices.

However, there are also progressive interpretations advocating for women's rights within the same religious framework. Overcoming these challenges requires fostering inclusive and respectful discourse, promoting education about gender equality, challenging patriarchal norms, and supporting policies that promote women's rights and equality in Pakistan and beyond.

The writer is a student of BS English Literature from the Government College University, Lahore.