As calls for reform echo through the years, skepticism emerges as a cautious companion, questioning the efficacy of change.

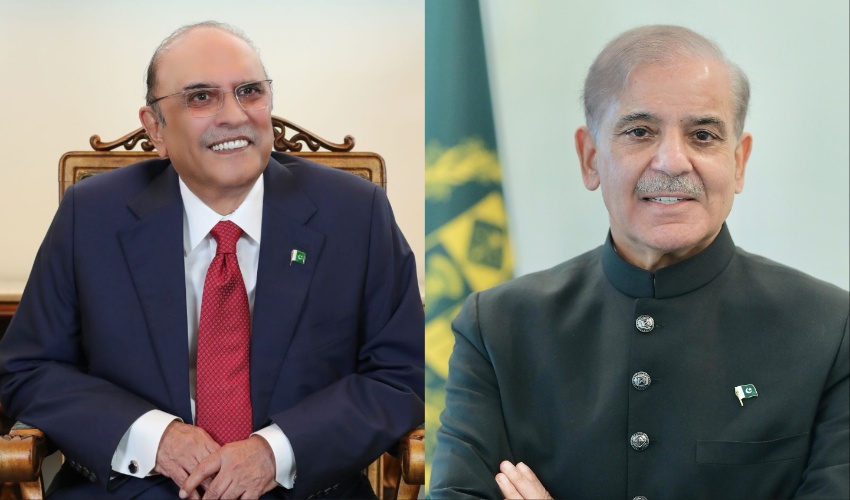

From the shadows of historical precedents to the corridors of modern era, Pakistan’s bureaucracy and political elites, or to call it the elite capture succinctly, have forged an unparalleled bond where they carefully watch each other’s interests, but at the cost of taxpayers hard-earned money.

Bureaucrats are very agile to respond to the needs of politicians, who in turn keep the floodgates of support open for their serving baboos. Governance reform has been a buzzword in Pakistan for years, with the need to establish transparent, accountable, and efficient organizations of administration gaining increasing prominence.

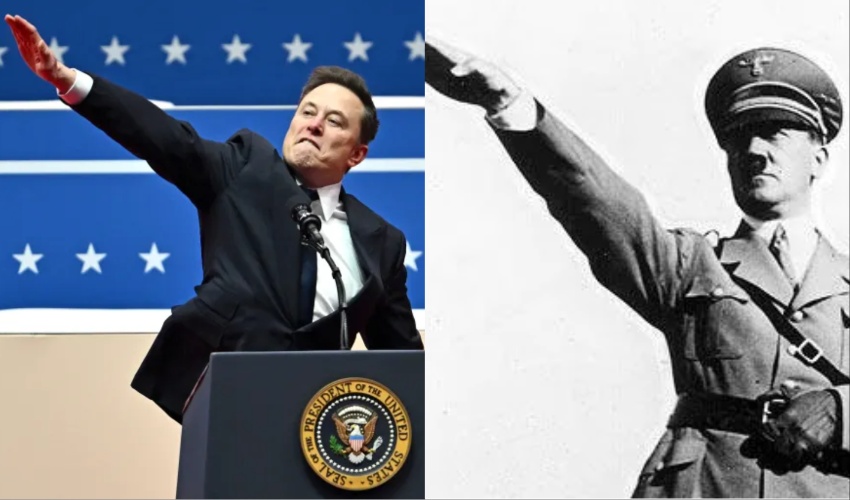

One of the critical aspects of governance that often faces scrutiny is the relationship between bureaucratic institutions and political associations. The nexus between bureaucracy and politics has been both a driving force for development and a breeding ground for corruption, leading to skepticism about the effectiveness of reforms.

The intertwining of bureaucratic and political forces in Pakistan can be traced back to its inception. The civil-military bureaucracy has played a significant role in shaping the country's political landscape. While this symbiotic relationship has occasionally resulted in progress, it has fostered a culture of patronage, nepotism, and corruption.

Political elites always come up with unforeseen allowances to the top bureaucrats, which are usually more than what a whopping 80% or more of the population earns a month -- a stark contrast to the economic conditions of the majority of Pakistan's population. These include executive allowance, utility allowance, and Secretariat allowance, among many others.

Moreover, bureaucrats benefit from a range of privileges such as drivers, cooks, luxury vehicles, free fuel, opulent accommodations, and more, all funded by taxpayers. Despite these privileges, there is a lack of accountability and performance audits for the bureaucracy.

Muhammad Ijaz, a former senior bureaucrat of repute, who served on multiple administrative positions as DCO and secretary in the Punjab and the federal capital, highlights this issue, stating that there has never been a proper evaluation of the bureaucrats' service delivery to the masses.

He points out that the bureaucratic-political partnership prioritizes the interests of its political masters over the well-being of the common man.

“There has never been a performance audit of these bureaucrats. There is no mechanism for evaluating their service delivery to the common man, who pays through the nose for their lavish lifestyles. They have an army of servants even to open the door or fix their chair,” Mian Ijaz remarks.

This political-bureaucratic nexus has put a spanner in the works of public service delivery. The Punjab Civil Servants Act 1974 and the Punjab Rules of Business 2011 are very clear about the service delivery aimed at facilitating the masses.

But, perhaps, these bureaucrats have deemed it appropriate to just read these Acts and Rules rather than applying them as basic demands of their jobs.

“There is an elite partnership between bureaucrats and politicians. They are least bothered about the miseries of the common man. When a bureaucrat gets a posting, transfer, allowances, bonuses through political manoeuvring, he/she is bound to carefully watch the interests of political masters,” Mian Ijaz laments, adding that the current state of affairs of the bureaucracy is at its lowest ebb with regards to serving the masses.

This nexus has been breeding corruption among bureaucrats and politicians, resulting in unmitigated sufferings of the people. For decades, Pakistan has had a prominent spot on Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index.

In theory, institutions like NAB and FIA were established as watchdogs to curb corruption and hold wrongdoers accountable. However, their effectiveness has been questioned over allegations of selective accountability and political interference.

Politicians are very vocal about curbing corruption and eliminating nepotism prior to any election to garner public support. But once in power, they realise that they have to work in tandem with the bureaucracy to get their illegal orders approved.

“Amidst the backdrop of promises for a transformed governance landscape, the cloud of skepticism continues to hover over the bureaucratic-political association. This scepticism has cast a shadow over the nation's pursuit of transparency and accountability,” says Mian Ijaz.

The Global Competitiveness Report 2022 indicates that corruption was among the top five problematic factors hindering doing business in Pakistan. This hampered economic growth, discouraged foreign investment, and perpetuated a cycle of poverty.

The former bureaucrat says the persistent skepticism surrounding bureaucracy-politics association has hindered any meaningful governance reforms. Public mistrust in the institutions' ability to bring about change has created apathy and disillusionment among citizens, posing a significant challenge to the government's efforts to enact transformative reforms. Despite the rhetoric, the resistance to change from within the bureaucratic and political circles also hampers progress.

While skepticism is justifiable given the historical context and repeated disappointments, it is essential to acknowledge that reform is a complex and gradual process. The government, civil society, and international partners must collaborate to rebuild trust in institutions and ensure that accountability mechanisms are independent and influential.

Moreover, fostering a culture of meritocracy and depoliticising appointments within the bureaucracy can help mitigate the corrosive effects of patronage.

Warnings regarding the perils that elite capture poses to Pakistan's future have garnered attention and concern from the World Bank, IMF, and prominent economists. The imperative need for Pakistan's power elites to embark on reforms is not merely an external suggestion but a necessity for safeguarding their own future in an evolving global landscape.

Stefan Dercon, a distinguished British economist, has aptly articulated that Pakistan's elites are ensnared in a relentless struggle for the control of resources and authority within a clientelist patronage state. Notably, their endeavours do not prioritize the nation's economic growth and development, which is a matter of profound significance, he maintains.

Beneath the surface, there exists a tacit agreement among influential elite factions, encompassing political leaders, business magnates, military figures, civil society luminaries, civil servants, intellectuals, and journalists, to maintain status quo.

Pakistan undeniably possesses an abundance of intellectual prowess and potential, but the crux of the issue lies at the intersection of politics and economics. These elite bargains predominantly revolve around governing access to resources and influential positions, perpetuating a systemic challenge that hinders progress and prosperity.

The bureaucracy-politics association in Pakistan has long been a source of contention, marred by corruption, patronage, and skepticism. Despite promises of reform, the country's journey towards transparent governance remains fraught with skepticism.

However, the way forward lies in collective efforts to rebuild trust, strengthen accountability, and gradually dismantle the culture of patronage. Only through sustained commitment can Pakistan navigate this intricate landscape and pave the way for a more transparent and accountable future.